Reanimating the Bones 3: Acid Nashville and Post-Neoliberalism

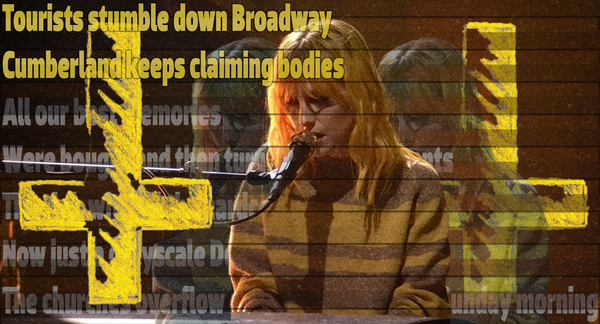

Hayley Williams's "True Believer" performance on Jimmy Fallon's show was a force. This third of several essays examines some of Williams's laments and hopes for Nashville.

This is the third mini-essay analyzing some of the lyrics and arrangement of Hayley William’s “True Believer”, a song from her newest solo album Ego Death At a Bachelorette Party, which she performed on Jimmy Fallon’s show in early October 2025.

If you’d like to read the introduction post to this series of posts, I wrote an intro you can read here:

The jumping off point for this essay is the middle lines in her first verse:

All our best memories

Were bought and then turned into apartments

The club with all the hardcore shows

Now just a greyscale Dominos

Erasing our Memories

The Muse was a south downtown all-ages punk bar that closed in 2012 before its 2015 rebirth as a Domino’s. While this specific Domino's doesn't appear to have received the ultramodern "greyscale" treatment many other fast food chains have, it is, like many properties on the outskirts of Nashville's downtown, once again listed as a "prime redevelopment opportunity."

As I wrote in the previous blog post on True Believer, the Lower Broadway district’s honky-tonk fantasy of drunken Midwestern bachelorette parties in cowboy cosplay appears to be the direction of Nashville all of those in power locally want to sell to the world and thus prioritize through policy. In that same post, I also mentioned Hayley Williams’s lamentation over policy hostile towards the poor and the unhoused.

Gentrification and the vagabondage of capital in contemporary socioeconomics touch on all three of these things: the erasure of the historic, the cheap commodification of Nashville’s identity, and a death cult targeting the poor. The reality is that this isn’t just a quirk of Nashville, though Nashville developers have recently begun to target similar developments in Chattanooga, nor is it unique to the South. However, the South of today, like the South of the last 50 years, has had politicians and developers willing to sell a city’s legacy wholesale, so long as there’s money to be made.

Like the Chattanooga project linked above, many of the housing developments (the “apartments” of the second line of this section of the first verse) in Nashville are built under mixed-use zoning, something that, in theory, is deeply beneficial to those wishing to live and work in an urbanized area. These builds often don’t take into account any of the details of the surrounding areas – from what historic site they might be bulldozing to who lives nearby to what materials are most common in nearby buildings. They may as well exist anywhere (or nowhere). Developers, architects, and business owners with few scruples are willing to take this mercenary work because of the return on investment or billable time offered with such projects. The tired formula of “Live. Work. Play.” threads across many of these projects, which ultimately take into account few--if any--lessons from urbanists of the past (like Jane Jacobs) and present alike. It truly is painful how often such projects follow the SoDoSoPa joke made by South Park a decade ago, which is used in that universe to argue for bringing a Whole Foods to the town.

The SoDoSoPa naming convention that South Park clocks is one present in Nashville, of course, which now refers to the area south of Broadway as SoBro, replete with lifestyle amenities one would come to expect in a gentrified neighborhood. The history of SoBro is a little darker, as much of SoBro, like many areas of Downtown Nashville (and indeed large parts of Nashville), was an area formerly known as “Black Bottom” that was targeted by so-called “slum clearance” during and before the wave of “urban renewal” in the mid-1900s. According to a senior capstone project by Caroline Knowles,

Downtown was an important site of Civil Rights activism in Nashville during 70 the 60s, and after the collapse of Black Bottom it began to be developed by white business owners and developers who saw low land costs due to the prior existence of Black Bottom as an advantage. Much of the area was completely cleared to make room for infrastructure that fit the image of what a “cleaner” Nashville looked like— a codified way of communicating that Downtown was not a neighborhood where Black residents were accepted.

Acid Nashville Beyond Neoliberalism

What Hayley laments with the Muse’s closure and its transformation into an ultra-modern pizza chain is just one of the many 21st-century battles that city residents and their representatives, planners, and business owners have been waging for decades. Her recognition in a lost past is one steeped in an acidic future, while held back by the forces of neoliberalism in Nashville. I borrow from Mark Fisher’s adjective “acid,” which he affixes as an adjective to describe a “spectre of a world that could be free.” Acidity, as Matt Colquhoun articulated in 2018, “resists definition…it is as difficult to define as ‘communism’ is in the 21st century.” As Stuart Mills explains in a Medium article he wrote in 2019, acid communism, to Fisher, could be described as the following: “The future has been cancelled because we are unable to imagine anything other than the present. To invent the future, to escape our myopia, we have to go beyond the present bounds of our imagination.” I’d also really encourage reading Cameron Summers’s 2020 reflections on acid communism (and a favorite video game of mine, Disco Elysium) as collected on the Broken Hands Media blog.

As capital investment ebbs and flows under urban neoliberalism, our spaces are impacted by overlapping and subsequent waves of redevelopment or revitalization or blight clearance, or whatever other word the policymakers are using at the time. This comes in the terms of development projects and exchange of investment property as the city continues to evolve. Hayley’s all-ages punk venue closed because it couldn’t keep up with rent and the repairs it needed to stay in business, and Domino’s selected the location likely as speculation on Nashville’s continued growth (and is now, as I said, a “prime redevelopment opportunity,” so the circle remains unbroken).

Ego Death at a Bachelorette Party is an album rich with mourning, but in this mourning comes imagination, knowing there is something else that is possible. Just as Williams sings in “Love Me Different,” describing therapy helping her come to terms it is herself that needs to love herself differently after a breakup, the urban erosion mourned in “True Believer” isn’t a death sentence; crucially, Nashville's flourishing can be reanimated. I keep coming back to this refrain in these essays for a reason – “I’m the one who still loves your ghost / I reanimate your bones / Cause I’m a true believer” is a hopeful (and acidic) view of Nashville’s situation and potential. Rather than casting Nashville as something completely lost and not worth lamenting, much less fighting for, this song uses a refrain to say our reality isn’t the endpoint.